Your DNA can help spot Parkinson's disease earlier than ever.

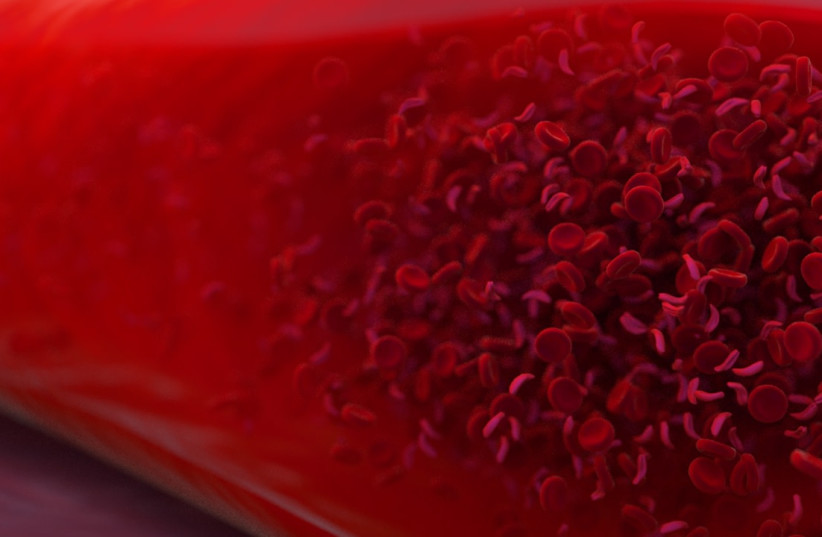

A new study has found that DNA damage, like that caused by Parkinson’s disease, can be spotted in the blood of rodents and the tissue of Parkinson’s patients.

Scientists may have found a new way to gain an early diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, according to a new study published late last month.

The peer-reviewed article, which is published in the academic journal Science Translational Medicine, chronicles the discovery of a blood test that may help people access brain cell-saving medication.

Often, diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease can take significant time. This can leave sufferers to experience progressively worsening fits of tremors, dementia, difficulty moving and other symptoms throughout the disease’s progression.

The new study has found that DNA damage, like that caused by Parkinson’s disease, can be spotted in the blood of rodents and the tissue of Parkinson’s patients.

While this research awaits further testing before it is available for widespread use, the new information “adds to our ability to state confidently that an individual has Parkinson’s disease or not,” said neurodegeneration researcher Mark Cookson to Science.org.

“It’s really exciting because it’s something [physicians] could use to detect [Parkinson’s] before the clinical symptoms emerge,” says neuroscientist Malú Tansey of the University of Florida, who also was not involved with the research,” the authors of the study wrote.

What is Parkinson’s disease?

Parkinson’s disease is a condition where neurons in the brain die, which causes the neurotransmitter dopamine to reduce its output. This can lead to a variety of conditions including muscle stiffness, balance problems, speech and cognitive problems, and a number of other issues.

It is believed that the cause of Parkinson’s is both genetic and based on environmental factors.

Parkinson’s often involves malfunctioning mitochondria, the powerhouse of the cell. Brain tissue from some Parkinson’s patients carries signs of mitochondrial DNA damage. Using this, and the knowledge that other researchers discovered defective mitochondria in patients’ blood cells, the researchers were able to discover mitochondrial DNA damage in blood “could be a surrogate for what’s happening in the brain,” explained neuroscientist Laurie Sanders.

The test, developed by Sanders’ team, was able to pick up on the disease-promoting variant of LRRK2, even among patients with no symptoms.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Stick to the subject, NO religion, or Party politics