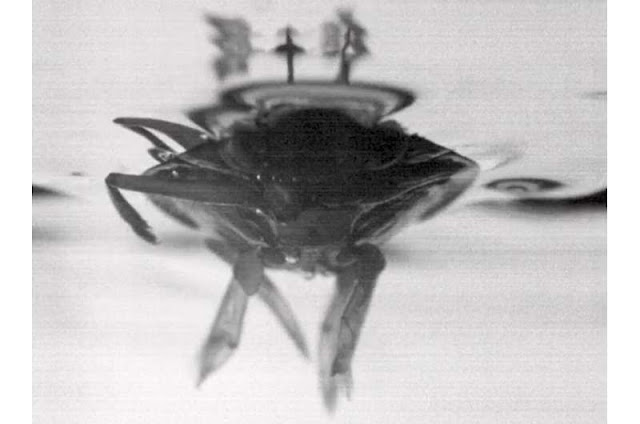

Credit: Cornell University

Whirligig beetles, the world's fastest-swimming insect, achieve surprising speeds by employing a strategy shared by speedy marine mammals and waterfowl, according to a new Cornell University study that rewrites previous explanations of the physics involved.

The centimeter-long beetles can reach a peak acceleration of 100 meters per second and a top velocity of 100 body lengths per second (or one meter per second).

Not only do the results explain the whirligig's Olympian speeds, but they also offer valuable insights for bio-inspired designers of near-surface water robots and uncrewed boats.

Until now, researchers have believed that whirligigs attain their impressive speeds using a propulsion system called drag-based thrust. This type of thrust requires the insect's legs to move faster than the swimming speed, in order for the legs to generate any thrust. For the whirligig beetle to achieve such fast swimming speeds, its legs would need to push against the water at unrealistic speeds.

"It could have well been questioned," said Chris Roh, assistant biological and environmental engineering professor. "The fastest swimmer and drag-based thrust don't usually go together in the same sentence."

In fact, fast-swimming marine mammals and waterfowls tend to forgo drag-based thrust in favor of lift-based thrust, another propulsion system. The finding was described in a study published Jan. 8 in the journal Current Biology.

See origional article for a vid of the bug swimming/flying through the water

Using two high-speed cameras synchronized at different angles, the researchers could film a whirligig and observe a lift-based thrust mechanism at play. Lift-based thrust works like a propeller, where the thrusting motion is perpendicular to the water surface, eliminating drag and allowing for more efficient momentum capable of greater speed.

"In biology, it's hard to rotate things," Roh said. "We're machines based on contraction. So, you could say the whirligig beetle's legs are a partial propeller that rotates about an angle and then they retract before they reset and rotate partially again."

Along with leg and body velocities extracted from two synchronized camera observations, Sun used aerodynamic formulations to calculate that a lift-based thrust accounted for most of the force required for the whirligig's speedy propulsion.

"It's not that different from an airplane wing being tilted a little bit," Roh said. "That angle of attack allows it to actually generate lift."

Lift-based thrust has previously been identified in large-scale organisms, such as whales, dolphins, and sea lions. "In this work, we extended the length scale down to one centimeter, which means that whirligig beetles are by far the smallest organism to use lift-based thrust for swimming," said Yukun Sun, a doctoral student in Roh's lab and the paper's first author.

"We're hoping that this speaks to bio-inspired robotics and other engineering communities first to identify the right physics and then try to preserve that physics in creating the robotics," Roh said.

The U.S. Navy has been developing uncrewed boats, as traditional ship design is constrained by the need to make boats hospitable to a crew. By eliminating a crew, boats can be much smaller and more flexible. Roh believes that the small size, ship-like shape, and lift-generating propulsion mechanism of whirligigs translate well to inform robotic ship designs.

Recommend this post and follow

The Life of Earth

No comments:

Post a Comment

Stick to the subject, NO religion, or Party politics