Neanderthals from two nearby caves cut meat in surprisingly different ways—revealing what might be the earliest signs of culinary culture.

Credit: Shutterstock

Bone cut-marks suggest Neanderthals had distinct food traditions—possibly even early “family recipes.”

A new study from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem has uncovered surprising clues about how Neanderthals prepared their food. Researchers found that two groups of Neanderthals living in neighboring caves in northern Israel, Amud and Kebara, butchered animals in noticeably different ways. Even though they used the same tools and hunted the same types of prey, the cut-marks left on bones show clear differences in technique.

These differences are not explained by skill level, tool design, or the availability of resources. Instead, they may point to cultural food traditions, such as drying or aging meat before cutting it. The study suggests that Neanderthals passed down specific food preparation methods through generations. This discovery offers rare insight into the rich social and cultural lives of our ancient relatives.

Credit: Anaelle Jallon

Cultural Clues in Butchery

Between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago, Neanderthals lived in two neighboring caves in what is now northern Israel: Amud and Kebara. They used similar stone tools and hunted the same types of animals. But a new study led by Anaelle Jallon from the Institute of Archaeology (with supervision from Rivka Rabinovich and Erella Hovers) and in collaboration with Lucille Crete and Silvia Bello from the Natural History Museum in London has revealed something unexpected.

By closely examining cut-marks on animal bones, the researchers found clear differences in how each group butchered its prey. These variations cannot be explained by differences in skill, tools, or resources. Instead, the evidence suggests that each group may have followed its own food preparation customs, possibly including practices like drying meat before cutting it.

Between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago, Neanderthals lived in two neighboring caves in what is now northern Israel: Amud and Kebara. They used similar stone tools and hunted the same types of animals. But a new study led by Anaelle Jallon from the Institute of Archaeology (with supervision from Rivka Rabinovich and Erella Hovers) and in collaboration with Lucille Crete and Silvia Bello from the Natural History Museum in London has revealed something unexpected.

By closely examining cut-marks on animal bones, the researchers found clear differences in how each group butchered its prey. These variations cannot be explained by differences in skill, tools, or resources. Instead, the evidence suggests that each group may have followed its own food preparation customs, possibly including practices like drying meat before cutting it.

Credit: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Neanderthal Family Recipes?

Could ancient humans have passed down cooking traditions? According to this new research, Neanderthals in the Amud and Kebara caves may have done exactly that. Despite living close to each other and relying on the same kinds of tools and animals, the two groups left behind very different butchery marks. This has led scientists to propose that they may have developed distinct food preparation styles that were shared within each community and handed down over time.

“The subtle differences in cut-mark patterns between Amud and Kebara may reflect local traditions of animal carcass processing,” said Anaëlle Jallon, PhD candidate at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and lead author of the article in Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology. “Even though Neanderthals at these two sites shared similar living conditions and faced comparable challenges, they seem to have developed distinct butchery strategies, possibly passed down through social learning and cultural traditions.

“These two sites give us a unique opportunity to explore whether Neanderthal butchery techniques were standardized,” explained Jallon. “If butchery techniques varied between sites or time periods, this would imply that factors such as cultural traditions, cooking preferences, or social organization influenced even subsistence-related activities such as butchering.”

Credit: Erella Hovers

A Tale of Two Caves

Amud and Kebara are close to each other: only 70 kilometers apart. Neanderthals occupied both caves during the winters between 50 and 60,000 years ago, leaving behind burials, stone tools, hearths, and food remains. Both groups used the same flint tools and relied on the same prey for their diet — mostly gazelles and fallow deer. But there are some subtle differences between the two. The Neanderthals living at Kebara seem to have hunted more large prey than those at Amud, and they also seem to have carried more large kills home to butcher them in the cave rather than at the site of the kill.

At Amud, 40% of the animal bones are burned, and most are fragmented. This could be caused by deliberate actions like cooking or by later accidental damage. At Kebara, 9% of the bones are burned, but less fragmented, and are thought to have been cooked. The bones at Amud also seem to have undergone less carnivore damage than those found at Kebara.

Amud and Kebara are close to each other: only 70 kilometers apart. Neanderthals occupied both caves during the winters between 50 and 60,000 years ago, leaving behind burials, stone tools, hearths, and food remains. Both groups used the same flint tools and relied on the same prey for their diet — mostly gazelles and fallow deer. But there are some subtle differences between the two. The Neanderthals living at Kebara seem to have hunted more large prey than those at Amud, and they also seem to have carried more large kills home to butcher them in the cave rather than at the site of the kill.

At Amud, 40% of the animal bones are burned, and most are fragmented. This could be caused by deliberate actions like cooking or by later accidental damage. At Kebara, 9% of the bones are burned, but less fragmented, and are thought to have been cooked. The bones at Amud also seem to have undergone less carnivore damage than those found at Kebara.

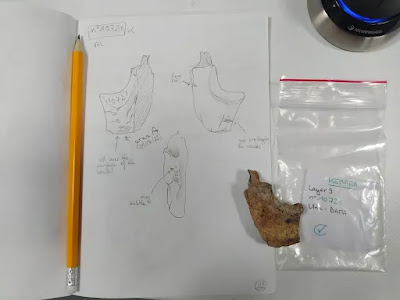

Credit: Anaelle Jallon)

Microscopic Investigations

To investigate the differences between food preparation at Kebara and at Amud, the scientists selected a sample of cut-marked bones from contemporaneous layers at the two sites. They examined these macroscopically and microscopically, recording the cut-marks’ different characteristics. Similar patterns of cut-marks might suggest there were no differences in butchery practices, while different patterns might indicate distinct cultural traditions.

The cut-marks were clear and intact, largely unaffected by later damage caused by carnivores or the drying out of the bones. The profiles, angles, and surface widths of these cuts were similar, likely due to the two groups’ similar toolkits. However, the cut-marks found at Amud were more densely packed and less linear in shape than those at Kebara.

To investigate the differences between food preparation at Kebara and at Amud, the scientists selected a sample of cut-marked bones from contemporaneous layers at the two sites. They examined these macroscopically and microscopically, recording the cut-marks’ different characteristics. Similar patterns of cut-marks might suggest there were no differences in butchery practices, while different patterns might indicate distinct cultural traditions.

The cut-marks were clear and intact, largely unaffected by later damage caused by carnivores or the drying out of the bones. The profiles, angles, and surface widths of these cuts were similar, likely due to the two groups’ similar toolkits. However, the cut-marks found at Amud were more densely packed and less linear in shape than those at Kebara.

Credit: Anaelle Jallon

Digging Deeper into the Data

The researchers considered several possible explanations for this pattern. It could have been driven by the demands of butchering different prey species or different types of bones — most of the bones at Amud, but not Kebara, are long bones — but when they only looked at the long bones of small ungulates found at both Amud and Kebara, the same differences showed up in the data. Experimental archaeology also suggests this pattern couldn’t be accounted for by less skilled butchers or by butchering more intensively to get as much food as possible. The different patterns of cut-marks are best explained by deliberate butchery choices made by each group.

Aging Meat and Group Roles

One possible explanation is that the Neanderthals at Amud were treating meat differently before butchering it: possibly drying their meat or letting it decompose, like modern-day butchers hanging meat before cooking. Decaying meat is harder to process, which would account for the greater intensity and less linear form of the cut-marks. A second possibility is that different group organization — for example, the number of butchers who worked on a given kill — in the two communities of Neanderthals played a role.

Unanswered Questions

“There are some limitations to consider,” said Jallon. “The bone fragments are sometimes too small to provide a complete picture of the butchery marks left on the carcass. While we have made efforts to correct for biases caused by fragmentation, this may limit our ability to fully interpret the data. Future studies, including more experimental work and comparative analyses, will be crucial for addressing these uncertainties — and maybe one day reconstructing Neanderthals’ recipes.”

The birth of modern Man

https://chuckincardinal.blogspot.com/

.webp)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Stick to the subject, NO religion, or Party politics