TAU researchers find link between electric voltage and brain adaptability

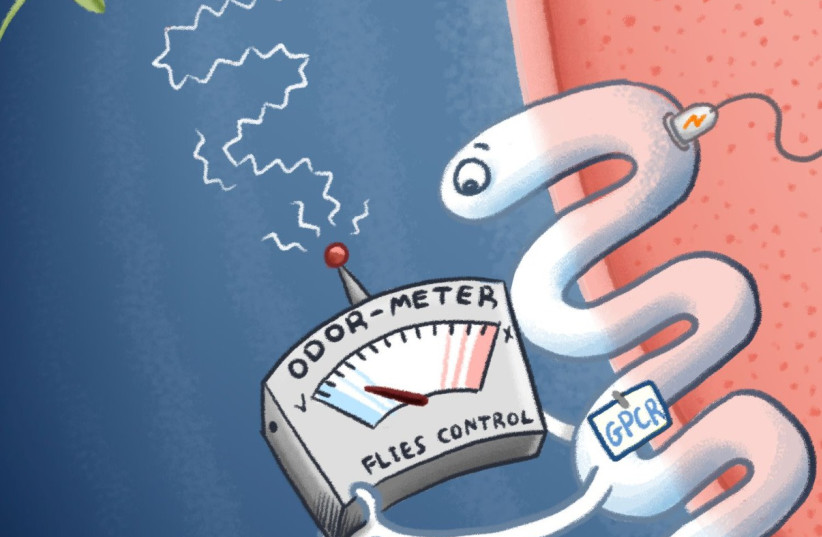

The researchers looked at the olfactory system of the fruit fly, examining whether the voltage dependence of GPCRs is significant to brain function.

In a novel study, researchers at Tel Aviv University’s

Sackler Faculty of Medicine and the Sagol School of Neuroscience have

discovered a direct link between changes in G-protein-coupled receptors

(GPCRs) and the brain’s ability to adapt to external changes. They found

that due to the brain’s mechanism, a few minutes after entering a room

containing a sharp odor, we stop smelling it.

The study, published recently in Nature Communications,

was conducted by Dr. Moshe Parnas and his team. It was a follow-up to

one conducted by his parents about two decades ago, which focused solely

on the protein level. The new study advances to the next stage.

The

researchers looked at the olfactory system of the fruit fly, examining

whether the voltage dependence of GPCRs is significant to brain

function. They focused on one receptor from the G protein-coupled

receptor family (called "Muscarinic Type A"). This protein is involved

in dependence to an odor, a process in which the intensity of the

reaction to the odor decreases as a result of continuous exposure to it.

Tel Aviv University Campus (credit: COURTESY TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY)

"Nerve cells are able to communicate with each other – and brain flexibility is expressed in the ability of nerve cells to set up new connections with each other and change existing connections, and thus influence behavior,” Parnas said. “Muscarinic Type A protein is involved in strengthening the bond between nerve cells, and strengthening of this bond causes fruit flies to get used to the odor and indicates normal brain flexibility."

THIS PAGE WAS POSTED BY SPUTNIK ONE OF THE SPUTNIKS ORBIT BLOG

PLEASE RECOMMEND THIS PAGE AND FOLLOW US AT:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Stick to the subject, NO religion, or Party politics