Whales move nutrients thousands of miles—in their urine—from as far as Alaska to Hawaii, supporting the health of tropical ecosystems and fish. (Humpback whale mother and calf.)

Credit: Martin van Aswegen, NOAA permit 21476

Whales do more than just swim the seas—they power the ocean’s ecosystem.

By transporting nutrients from deep waters to the surface and across vast distances, they fuel marine life in ways we’re only beginning to understand. Their migrations bring nitrogen-rich urine and organic matter to nutrient-starved tropical waters, boosting plankton, fish, and coral reefs. Once decimated by whaling, whale populations are rebounding, revealing the crucial role these giants play in planetary nutrient cycles.

Whales: The Ocean’s Nutrient Movers

Whales aren’t just massive—they play a massive role in keeping oceans healthy. When they defecate, they transport nutrients from deep waters to the surface. Now, new research shows they also move vast amounts of nutrients thousands of miles—through their urine.

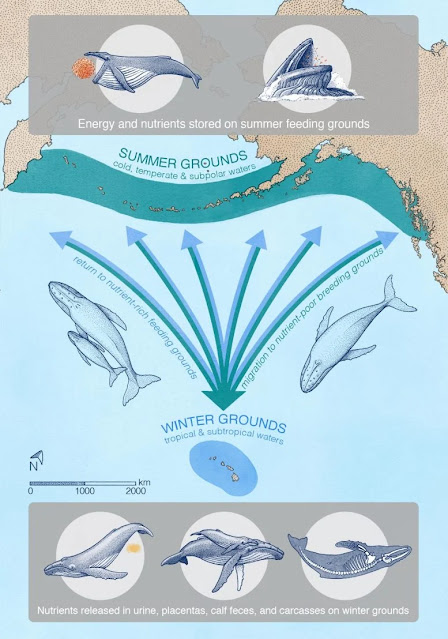

Scientists showed in 2010 that whales feeding at depth and excreting waste at the surface help fertilize the ocean, boosting plankton growth and marine productivity. But a new study led by the University of Vermont reveals that whales also transport nutrients across entire ocean basins. As they migrate from nutrient-rich, cold feeding grounds to warm tropical waters where they breed and give birth, they release these nutrients—primarily through their urine, but also via sloughed skin, feces from calves, placentas, and even their carcasses.

Boosting Coastal and Coral Ecosystems

“These coastal areas often have clear waters, a sign of low nitrogen, and many have coral reef ecosystems,” says Joe Roman, a biologist at the University of Vermont, who co-led the new research. “The movement of nitrogen and other nutrients can be important to the growth of phytoplankton, or microscopic algae, and provide food for sharks and other fish and many invertebrates.”

Published today (March 10) in Nature Communications, the study estimates that great whales—including right whales, gray whales, and humpbacks—deliver approximately 4,000 tons of nitrogen each year to nutrient-poor tropical and subtropical coastal waters. In addition, they contribute over 45,000 tons of organic material. Before large-scale whaling drastically reduced their populations, this nutrient transport may have been three times greater, underscoring the vital role whales once played—and may play again—in ocean ecosystems.

Many whales travel thousands of miles from their summer foraging areas to winter grounds for breeding and calving. Nitrogen and other elements can be released in the form of urine, carcasses, placentas, sloughing skin, and feces (primarily from nursing calves). Humpback whales of the Central North Pacific, shown here, primarily feed off the coast of Alaska and spend winters in the shallow waters of the Hawaiian archipelago.

Credit: Illustration by A. Boersma; text adapted from original study in Nature Communications

A Giant Conveyor Belt of Life

For example, thousands of humpback whales travel from a vast area where they feed in the Gulf of Alaska to a more restricted area in Hawaii, where they breed. There, in the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary, the input of nutrients—tons of pee, skin, dead bodies and poop—from whales roughly double what is transported by local physical forces, the team of scientists estimate.

“We call it the ‘great whale conveyor belt,” Roman says, “or it can also be thought of as a funnel because whales feed over large areas, but they need to be in a relatively confined space to find a mate, breed, and give birth. At first, the calves don’t have the energy to travel long distances like the moms can.”

Plus, the whales probably stay in shallow, sandy waters because it muffles their sounds. “Moms and newborns are calling all the time, staying in communication,” says Roman, a conservation researcher in the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources and fellow in UVM’s Gund Institute for Environment “and they don’t want predators, like killer whales, or breeding humpback males, to pick up on that.”

This means that nutrients spread out over the vast ocean are concentrated in much smaller coastal and coral ecosystems, “like collecting leaves to make compost for your garden,” Roman says.

A High-Stakes Journey Without Food

In the summer, adult whales feed at high latitudes (like Alaska, Iceland, and Antarctica), putting on tons of fat, chowing down on krill and herring. According to recent research, North Pacific humpback whales gain about 30 pounds per day in the spring, summer, and fall. They need this energy for an amazing journey: baleen whales migrate thousands of miles to their winter breeding grounds in the tropics—without eating.

For example, gray whales travel nearly 7000 miles between feeding grounds off Russia and breeding areas along Baja California. And humpback whales in the Southern Hemisphere migrate more than 5000 miles from foraging areas near Antarctica to mating sites off Costa Rica, where they burn off about 200 pounds each day, while urinating vast amounts of nitrogen-rich urea. (One study in Iceland suggests that fin whales produce more than 250 gallons of urine per day when they are feeding. Humans pee less than half a gallon daily.)

Whales undertake the longest migration of any mammal in the world. And whales are gigantic. “Because of their size, whales are able to do things that no other animal does. They’re living life on a different scale,” says Andrew Pershing, one of ten co-authors on the new study and an oceanographer at the nonprofit organization, Climate Central. “Nutrients are coming in from outside—and not from a river, but by these migrating animals. It’s super-cool, and changes how we think about ecosystems in the ocean. We don’t think of animals other than humans having an impact on a planetary scale, but the whales really do.”

What We’ve Lost and What We Can Learn

Before industrial whaling began in the nineteenth century, the nutrient inputs would have “been much bigger and this effect would’ve been much bigger,” says Pershing. Plus, the nutrient inputs of blue whales—the largest animals to ever live on the Earth—are not known and were not included in the primary calculations of the new study.

In the Southern Ocean, blue whale populations are still greatly reduced after intense hunting in the twentieth century. “There’s basic things that we don’t know about them, like where their breeding areas are,’’ said Pershing, “so that’s an effect that’s harder for us to capture.” Both blue whales and humpbacks were depleted from hunting, but some humpback and other whale populations are rebounding after several decades of concerted conservation efforts.

“Lots of people think of plants as the lungs of the planet, taking in carbon dioxide, and expelling oxygen,” says Joe Roman, “For their part, animals play an important role in moving nutrients. Seabirds transport nitrogen and phosphorus from the ocean to the land in their poop, increasing the density of plants on islands. Animals form the circulatory system of the planet—and whales are the extreme example.”

The Life of Earth

Ancient peoples knew the principals of the cycle of Life, long ago. I guess what is old becomes new again

ReplyDelete